Anatomy of Market Failure IV: Ostrom and Governance

Property rights, use rights, and institutional diversity

Sheep grazing on a pasture in Shropshire

Almost all discussions about energy and environment economics and policy invoke the market failure concept, either explicitly or implicitly: market prices don't reflect external costs of emissions, firms don't have strong R&D incentives because there's market failure in innovation, and so on. Often such claims lead to normative institutional conclusions: the federal government should institute a tax on emissions, should subsidize R&D ...

All claims about market failure are claims about property rights, and the framing of those property rights claims influences the institutional choices people make as policymakers. Armen Alchian's essay in the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics provides a good definition of this concept:

A property right is the exclusive authority to determine how a resource is used, whether that resource is owned by government or by individuals. Society approves the uses selected by the holder of the property right with governmental administered force and with social ostracism. If the resource is owned by the government, the agent who determines its use has to operate under a set of rules determined, in the United States, by Congress or by executive agencies it has charged with that role.

Private property rights have two other attributes in addition to determining the use of a resource. One is the exclusive right to the services of the resource. Thus, for example, the owner of an apartment with complete property rights to the apartment has the right to determine whether to rent it out and, if so, which tenant to rent to; to live in it himself; or to use it in any other peaceful way. That is the right to determine the use. If the owner rents out the apartment, he also has the right to all the rental income from the property. That is the right to the services of the resources (the rent).

Finally, a private property right includes the right to delegate, rent, or sell any portion of the rights by exchange or gift at whatever price the owner determines (provided someone is willing to pay that price). If I am not allowed to buy some rights from you and you therefore are not allowed to sell rights to me, private property rights are reduced. Thus, the three basic elements of private property are (1) exclusivity of rights to choose the use of a resource, (2) exclusivity of rights to the services of a resource, and (3) rights to exchange the resource at mutually agreeable terms.

If you have property in something, you can use it as you see fit, lend it to someone, give it away, let it sit idle, rent it out, or sell it. Without a concept of property and legal institutions backstopping the definition and enforcement of property, mutually-beneficial exchange cannot occur (and we'd be in Hobbes’ mythical state of nature). Property relies on a combination of formal (legal) and informal (norms) institutions. [Nota bene: if you are interested in these ideas, Bart Wilson’s book The Property Species is a fascinating account of the concept of property; following Hume, Bart argues that property emerges in society as a convention to foster peace and prosperity.]

Pigou’s foundational externality model assumed a specific set of property rights in his “polluter pays” framework. Coase criticized that assumption and argued that legal clarity of property rights combined with low transaction costs enables people to trade their rights, a discovery process leading to least-cost harm reduction. Buchanan & Stubblebine start from the acknowledgement that property rights will generally not be fully defined; that fact creates interdependencies that lead to external costs and benefits, but not all such externalities should be addressed to achieve economic efficiency.

Another way of saying it is that “market failure” problems are problems of ill-defined property rights. But it doesn't necessarily follow that ill-defined property rights necessitate regulation or some other form of government intervention. The existence of ill-defined property rights does not imply a specific institutional approach. The place to see that most clearly is in common-pool resources (CPRs), and the person whose work illuminates the diversity of institutional alternatives the best is Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom.

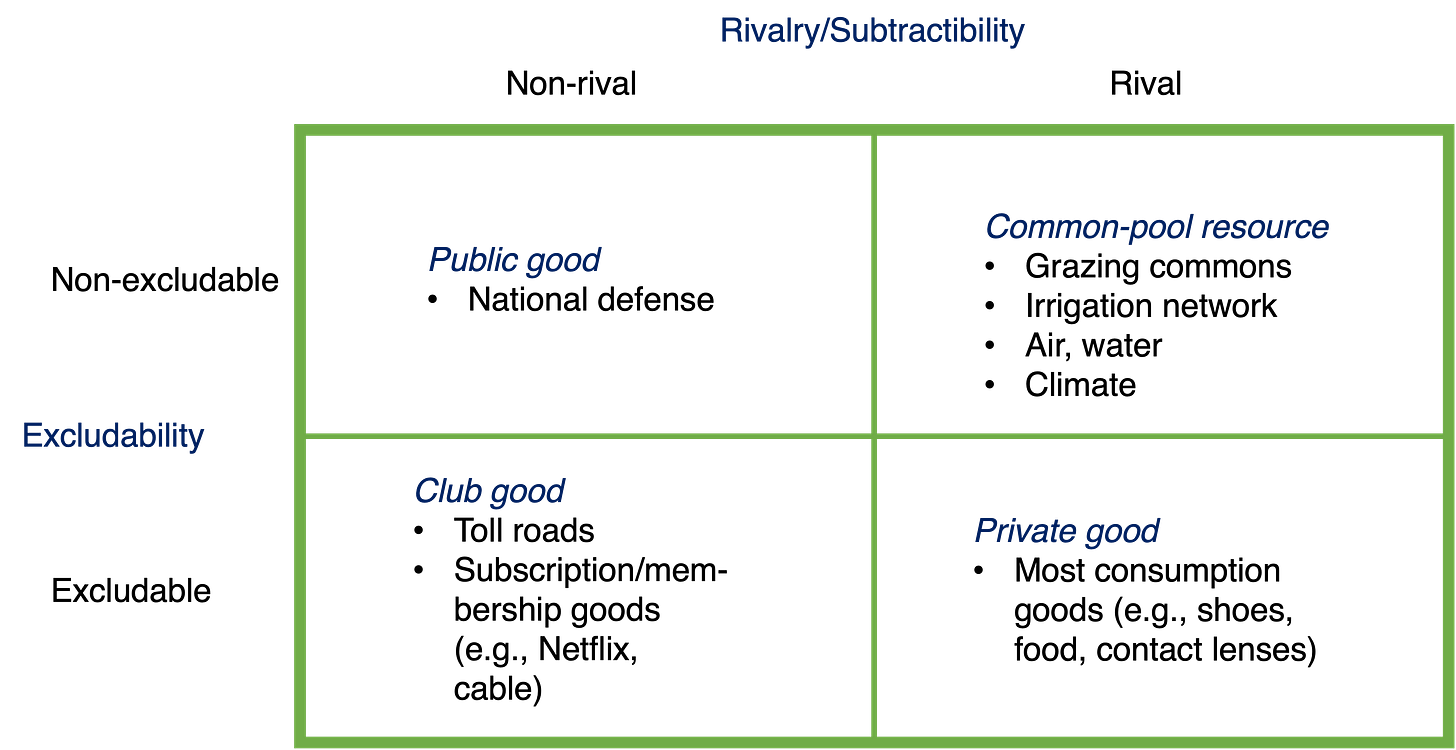

A CPR is a resource over which defining and enforcing property rights is costly or not feasible, so the resource is used in a shared way as a commons. In the language of public goods, a CPR is nonexcludable but rival/congestible/has capacity constraints. Surface streets and non-toll highways are CPRs. Airsheds and watersheds are CPRs. Irrigation networks, and indeed most networks in general are CPRs (and I'll have a lot more to say on that at some point). The global climate is a CPR.

The canonical example of a CPR, from Garret Hardin’s classic work Tragedy of the Commons (1968), is a shared grazing pasture in an English medieval village. The agricultural productivity benefits of shared large-field farming practices meant that consolidating and fencing individual plots to graze personal cattle was not worth it; instead the custom evolved into using large fallow fields as shared grazing commons. The challenge, or tragedy (as Hardin named it) of the commons is that each villager has an incentive to add another head of cattle to the field. Once the number of cattle reach the field’s carrying capacity, each additional head of cattle reduces the grass available to all, but each person only bears a small portion of that cost while being able to have an additional head of (underfed) cattle. The ubiquity of this incentive leads to all villagers adding cattle to the field beyond its capacity, resulting in overgrazing, erosion, pest infestations, reduction in soil quality, and eventually in starving cattle and sterile land. This situation is also known as a collective-action problem because each individual’s incentive to act is not aligned with the actions that would create the greatest aggregate benefit. The lack of alignment is a direct consequence of the costliness or inability to define and enforce property rights.

Elinor Ostrom’s pioneering, Nobel-winning research into CPRs shed light on the continuing practice of CPR governance; the best place to start is Governing the Commons (1990). Unlike Hardin’s gloomy tragedy, Ostrom found successful commons governance through extensive field research, studying CPR governance practices in Cambodian rice farming villages, fishing villages around the world, and other situations in which people shared use of a resource that could be depleted or destroyed if not used sustainably. She and her colleagues found repeatedly that when the users of a CPR developed a governance framework, either by custom or by deliberate design (or a hybrid of the two), they could avoid the tragedy of the commons, or what's more accurately called the tragedy of open access. Ostrom's work revealed the diversity of institutions, how governance institutions vary depending on the situation and the problem to be resolved, and that bottom-up community self-governance can use local knowledge to resolve commons problems more effectively than top-down external imposition of regulation from outside the community.

Such governance frameworks rely on the recognition that property rights in the resource are ill-defined, and that defining them is either costly or not feasible, so CPR users instead have “use rights”, a right to use the CPR in a defined way, that can overcome collective-action problems. These use rights can emerge from custom (such as the emergence of prior appropriation use rights in irrigation networks in the American West (Leonard & Libecap 2016)), from deliberate rules, or, most often, from a hybrid where rules formalize customary practices that have stood the test of time.

Ostrom’s work also delved into how governance frameworks should be structured depending on the nature of the CPR issue, and what the characteristics of communities were that made them more or less likely to be able to use community self-governance to achieve sustainable CPR use. A final aspect of CPR governance relevant to environmental policy is insight from both Elinor Ostrom and her husband, political scientist Vincent Ostrom, on the value of polycentric governance. Polycentricity means that multiple different authorities coexist simultaneously within a layered rules framework (Ostrom, Tiebout, & Warren (1961). This layered approach to governance means that institutions and outcomes can emerge through evolution and adaptation as circumstances change and as people learn from experience in the existing institutions. Polycentric governance institutions are especially well-suited to highly complex situations, with resource diversity, lots of people, and complicated interactions leading to the problem or harm in question. For complex CPR problems, polycentric governance at different layers and taking different approaches (e.g., more or less formalized, more or less self-governance) may yield more beneficial outcomes than either a monolithic top-down regulatory approach or bottom-up community self-governance; here's Ostrom's outstanding book Understanding Institutional Diversity is an essential resource.

Ostrom’s governance framework rests on the fundamental concept of property rights, but modifies the concept to the CPR context in which property rights definition and enforcement are either too costly or not feasible. In this context, governance entails specifying the scope and boundaries of the CPR, defining the permitted participants/users, and defining the use rights that the users have in the CPR. For example, in a shared community irrigation system, the water is scarce and its availability varies over time. A CPR governance institution would specify the boundaries of the irrigation system and the community members who have rights to withdraw from it. It would also define as a use right how much water each member can withdraw.

This logic of acknowledging the ill-defined property rights that make something a CPR while using a governance institution to define and enforce use rights has wider policy relevance than just irrigation systems. Examples of environmental CPR issues include management of resources like fisheries and forests, air pollution, water pollution, urban noise pollution, irrigation systems, and climate. Global climate is a CPR in the sense that property rights in the climate are necessarily ill-defined or not feasible, with a resulting collective-action problem that individually beneficial actions can lead to systemic adverse outcomes. Ostrom’s climate-focused work argued for developing polycentric efforts to reduce the risks associated with greenhouse gas emissions, rather than sole emphasis on global climate policies; see, for example, Nested externalities and polycentric institutions: Must we wait for global solutions to climate change before taking actions at other scales? (Economic Theory 49, no. 2 (2012): 353-369). National, state-level, and local formal rules and informal norms can coexist and create different pathways for greenhouse gas reduction.

Ostrom's work illustrates why bringing nuance to the use of the “market failure” concept is so essential, why contextualizing discussions of market failure clearly in a property rights framework is so important, and why allowing for institutional diversity and not only administrative government regulation can yield better outcomes, more human flourishing, and more effective approaches to environmental policy. If you are unfamiliar with her work I cannot recommend it to you highly enough.

Given China's radical, creative and successful approach(es) to such matters, I am surprised that we see so little discussion of the country in this context.

Are our scholars being discouraged from studying the Middle Kingdom?

"Thus, for example, the owner of an apartment with complete property rights to the apartment has the right to determine whether to rent it out and, if so, which tenant to rent to; ...."

So this gives the owner the right to discriminate against people of color, religion, sexual orientation or ethnicity? Lynn, are you seriously suggesting that this is a good idea?

I'm a staunch supporter of economic efficiency and market mechanisms but I also believe that a society collectively needs to look at market outcomes with jaundiced eye and decide whether it likes what it sees.

Markets are agnostic and amoral. They may (or may not) produce outcomes that are efficient but markets have no conscience. It is naive to believe that whatever outcome a market produces is necessarily good,

Sorry, but Hayek was wrong.