Economic Foundations: Natural Monopoly Theory I

What is a natural monopoly, and is that model useful under technological dynamism?

Every day seems to bring a new energy technology announcement (there are three links there, don't miss them!). With the diverse and turbulent technological changes under way affecting electric systems, a firm foundation in economic principles can help us make better decisions in the face of unknown and changing conditions – better policy decisions, regulatory decisions, investment decisions, consumption decisions. One of my goals with this weekly newsletter is to provide digestible, accessible nuggets of those foundational principles.

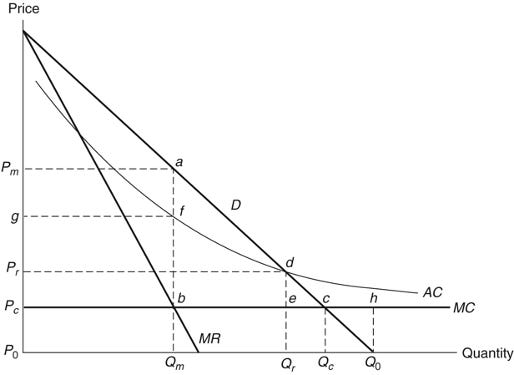

Economics is, and always has been, important for understanding the electricity industry. The industry's commercial development in the 1880s pre-dates the formal economic theory that's usually associated with electricity: natural monopoly theory. Natural monopoly theory starts with the basic market model, with a competitive equilibrium where price equals marginal cost (P=MC) as the benchmark against which to evaluate other possible outcomes. The other benchmark, the monopoly model, is a market with a single supplier that can exercise its market power to charge a price well above MC, sell less output, and make higher profits by doing so while also creating waste (aka deadweight loss) due to the lost surplus from having fewer transactions.

The twist in natural monopoly theory is that the underlying cost structure of firms in the industry is not "nice". Average cost per unit of output doesn't have the nice U-shape of falling when output is low and the supplier is creating and exploiting its economies of scale, then bottoming out, and then increasing again as the diseconomies of operating a large firm kick in. Instead, average cost declines "over the relevant range of demand", meaning that the least-cost way to meet demand is to have a single firm produce all of the output, and that a market with multiple rivals will consolidate and converge to a single firm. What causes that declining average cost curve? Typically a combination of high fixed costs and low variable costs, so it's not surprising that economists developed the natural monopoly model to structure their thinking about the new capital-intensive industries of the mid- to late-19th century: first water, then railroads, then telegraph and telephone, and at the turn of the 20th century, electricity. This model informed the nascent regulatory public utility commissions in the early 20th century and has been enshrined in the regulatory model and the utility business model ever since.

Technically, the challenge is that high fixed costs for building power plants, poles and wires, and substations swamp the relatively low variable costs of fuel and labor, so when a firm produces more output, its average cost falls by spreading those fixed costs over lots more units of output. But firms with this cost structure will never have positive profit from selling in a competitive equilibrium at P=MC, so they have to charge a higher price to cover their fixed costs. How high is too high? This question plagues electricity policy to this day, as my past two essays (two links!) have indicated. In this sense the economists developing the natural monopoly concept concluded by the early 20th century that the natural monopoly cost structure was incompatible with the benchmark "perfect" competition equilibrium at P=MC, since to break even they have to earn price equal to average cost (AC). This is the conundrum of high fixed cost industries.

How did we get here? I cannot recommend highly enough Manuela Mosca's article, On the origins of the concept of natural monopoly: Economies of scale and competition (European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 2008). Mosca traces the idea of natural monopoly from its conceptual origins and association with a physical, spatial production advantage to its modern definition rooted in technological characteristics of production. While Adam Smith referred to this physical advantage, Malthus was the first to use the phrase "natural monopoly" in reference to it (Mosca p. 322). These early ideas combine what we now think of as comparative advantage with a limit on the spatial extent of the market.

Starting with John Stuart Mill in the 1840s, the concept sharpens and focuses on technological characteristics that affect production costs, and (glossing over a lot of important and interesting details in her article) by 1911 the British economist F. Y. Edgeworth's analysis of railroads provides a reasonably complete articulation of the incompatibility of a natural monopoly cost structure with the benchmark "perfect" competition equilibrium at P=MC. He's also the person who systematized the relationship among total cost, average cost, and marginal cost, building on Alfred Marshall's pioneering work from two decades earlier. The American economist Richard Ely contributed to this literature in the late 1880s-1890s with concrete applications to new industries like telephones and electric lighting, and with a more normative advocacy-activist objective. [A brief institutional aside: Ely, a faculty member at the University of Wisconsin, would have a graduate student named John Commons who, working with Robert LaFollette, wrote the groundbreaking legislation in Wisconsin that established the first state Public Utility Commission in 1907 to regulate these natural monopoly industries "in the public interest".]

These capital-intensive infrastructure industries were new and growing fast in the late 19th century. One of Mosca's conclusions is that

We are facing a typical case of economic thought shaped by reality. In fact the spread of the expression ‘natural monopoly’ in its current meaning, and the consolidation of the related theory, came about mainly with the spread of the situation that could be described as natural monopolies. For instance, when Ely says that ‘various undertakings . . . are monopolies by virtue of their own inherent properties’, he also specifies that ‘these undertakings are nearly all of them comparatively new’ (1894: 294) (p. 346).

These "inherent properties" are technological determinants of the cost structure of production.

The seemingly simple idea of declining average cost over the relevant range of demand comprises several details and assumptions that turn out to be pretty important. In this market the product being transacted is assumed to be homogeneous (although some later 20th century literature introduces product differentiation). The cost structure is known and common to all current and potential suppliers of the homogeneous good, which means that the production technology set is fixed and common. Market demand is fixed. This model is a static, snapshot representation of an abstraction of an underlying dynamic system.

By the 1970s, all of these assumptions would be violated in the electricity industry. And they were violated so strongly and rapidly in telecommunications that by the mid-2000s state public utility regulation was barely relevant.

As George Box famously said, all models are wrong but some are useful. My question for you is: How useful do you think this static neoclassical natural monopoly model is for understanding 21st century technological change in electricity and for informing regulatory theory and practice?

In Part II of these musings on natural monopoly theory I'll discuss work from the 1970s and 1980s critiquing this static model and trying to make it more dynamic.

What?! Malthus came up with the phrase "natural monopoly?" Amazing!