Discover more from Knowledge Problem

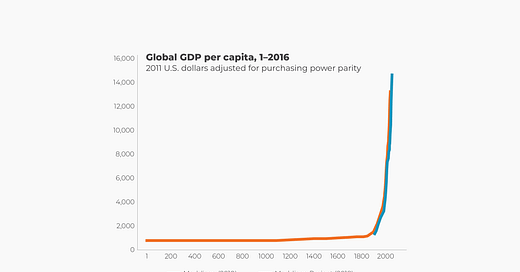

A paradox of our considerable relative wealth is that the 21st century culture is generally pessimistic. Whether it’s inequality, climate change, or particular economic issues like high housing costs in urban areas, the vibes are anti-progress, and have been for some time. Yet the increasing prosperity of the past 250 years is remarkable, particularly when compared to relatively stagnant past human history. The well-known GDP per capita estimates since the year 1 from Angus Maddison, embodied in the famous hockey stick graph, indicate just how remarkable modern prosperity is in human history:

Source: Human Progress

Yes, the data get spottier the further back in time they go, and yes, there are substantial regional variations in this prosperity over time, with China having an early efflorescence and then the great divergence between China and Western Europe starting in the 18th century, with the United States growth blossoming in the 19th century. But evidence is incontrovertible for what Deirdre McCloskey calls the great enrichment, the dramatic growth of living standards, life expectancies, and per-capita incomes since the 18th century.

For the past five decades, really starting with David Landes’ essential work The Unbound Prometheus in 1969, research in economic history has focused on understanding the causes of such substantial economic growth in Western Europe and the US, and particularly Britain's role in industrialization. Not surprisingly, given that economic activity is such a complex phenomenon, the more we learn the more complicated the possible causal story becomes. The list is long: natural resource endowments in food, energy, and minerals, skilled labor supply (upper-tail human capital), birth rate differences leading to changing demographics, commerce and capital-labor substitution due to relative input prices, the fragmented and relatively liberalized institutional structure in Europe, Britain's constitutional constraints on government finance, Britain being an island and thus hard to invade, changing acceptability of bourgeois values in the Netherlands and Britain, innovation in agricultural practices, innovation in shipping technologies, innovation innovation innovation.

In my admittedly biased assessment, the explanation I find most compelling comes from Joel Mokyr (full disclosure: Joel was my Ph.D. advisor and continues to be a dear friend and deep influence on me). In A Culture of Growth (2016), Mokyr gathers evidence to argue that particular aspects of culture and ideas in early modern Europe and the European Enlightenment laid the foundations for subsequent technological change, innovation, and industrialization. Knowledge creation was a behavior in ascendance in the 17th century, particularly in Britain and the Netherlands, and a pan-European “Republic of Letters” provided a social norm of widespread knowledge sharing (and receiving reputation capital from the credit for knowledge creation). As this behavior expanded so did the knowledge and basic understanding of the physical world, grounded in scientific methods and empiricism codified by Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626). Formal organizations like the Royal Society in Britain provided a focal point for meeting, presenting, peer reviewing, and publishing among knowledge creators (natural philosophers in the language of the time). High literacy rates in Britain meant that this knowledge reached more people than just the natural philosophers, and in particular reached farmers, artisans, and tinkerers who used this new knowledge to improve their existing practices and invent new methods, new tools, new equipment, and ultimately new machines. All of this diffuse activity pre-dated what we think of as the beginnings of industrialization in the mid-18th century, and in Mokyr’s argument these cultural, cognitive, and institutional foundations create the possibilities for the subsequent technological changes and innovations in various industries, including the early Industrial Revolution heavy hitters of textile manufacturing, water and steam energy generation, and large-scale iron manufacturing. Britain was well-suited to turning propositional knowledge from the Scientific Revolution into useful knowledge that created the Industrial Revolution.

A new working paper provides useful evidence for Mokyr’s hypotheses. Enlightenment Ideals and Belief in Progress in the Run-up to the Industrial Revolution: A Textual Analysis, by Ali Almelhem (World Bank), Murat Iyigun (University of Colorado Boulder), Austin Kennedy (University of Colorado Boulder), and Jared Rubin (Chapman University), combines archival work with detailed data analysis and machine learning techniques to show how the language of science changed over time (1500-1900) to become more secular and more progress-oriented. They also demonstrate the concentration of this progress sentiment in volumes dedicated to industrial knowledge. I was fortunate to attend Jared Rubin’s presentation of this paper in the Northwestern University economic history seminar in the fall, and it’s a careful, thorough, thoughtful, and creative piece of research.

The paper sets out to test Mokyr's hypotheses:

The evidence Mokyr presents is abundant and convincing. Yet, there are two margins on which evidence is lacking. First, while the attitudes of elite thinkers and scientists were clearly becoming more progress-oriented in this period, it is far from clear that these ideas spread to those artisans and craftsmen who ended up becoming the driving force of Britain’s Industrial Revolution. It is certainly important that elite thinkers held progress-oriented views—upper-tail human capital has been shown to be an important precursor of industrialization (Squicciarini and Voigtlander 2015)—but the “Industrial Enlightenment” was largely advanced by artisans and those with closer ties to industry. Second, qualitative evidence by construction cannot account for the hundreds of thousands of works produced in this period. Is it possible to marshal quantitative evidence that the language of science became more progress-oriented in this period? If so, such evidence may provide insights that elude qualitative studies. (p. 2)

They perform a textual analysis of English-language documents digitized in the HathiTrust collection and written 1500-1900. Using over 173,000 unique documents they can test word frequency (but not adjacency and therefore not phrases) to see how language use changed over time in works in three areas: religion, science, and political economy. They find that the language of science did change in early modern Britain, becoming more secular and less religious. They also perform a sentiment analysis across works and topics, and find that progress sentiments are concentrated in science and political economy texts and increase in the 18th and 19th centuries. Finally, they concentrate specifically on industrial texts and find progress sentiments in texts designed to communicate useful, applied knowledge, not just basic propositional knowledge. They also perform a qualitative analysis of some early 18th century texts to demonstrate the creation of useful knowledge. One of my favorites was when they quoted Martin Clare’s (1735) book on fluid motion and its application to siphons, pumps, and engines; Clare intended his audience to put this knowledge to productive use:

The young Philosopher may be assisted hereby, in his first Searches after truth: Besides which Advantage, his Mind will be better prepared for receiving Lectures in Natural and Experimental Philosophy; which, with proper Encouragement, might easily be introduced into Societies, and made of singular Use and Benefit to Mankind. (p. vii)

The paper is well-written and easy to read, and I recommend it to you if you are curious about the details of how, and how well, they applied the machine learning and sentiment techniques to analyze such a large and rich set of historical data. It concludes with a suggestion for further work:

Likewise, similar techniques can be applied to the corpus of works in other languages. For instance, works by McCloskey (2006, 2010, 2016) suggest that similar results should be found in the corpus of works written in Dutch. Meanwhile, this was the period where the Spanish economy began to lag behind the leaders of Europe, while Spain was also the vanguard of the Counter-Reformation. Whether these economic and political phenomena are reflected in the cultural attitudes regarding progress and science remains a fruitful avenue for future work. (p. 35)

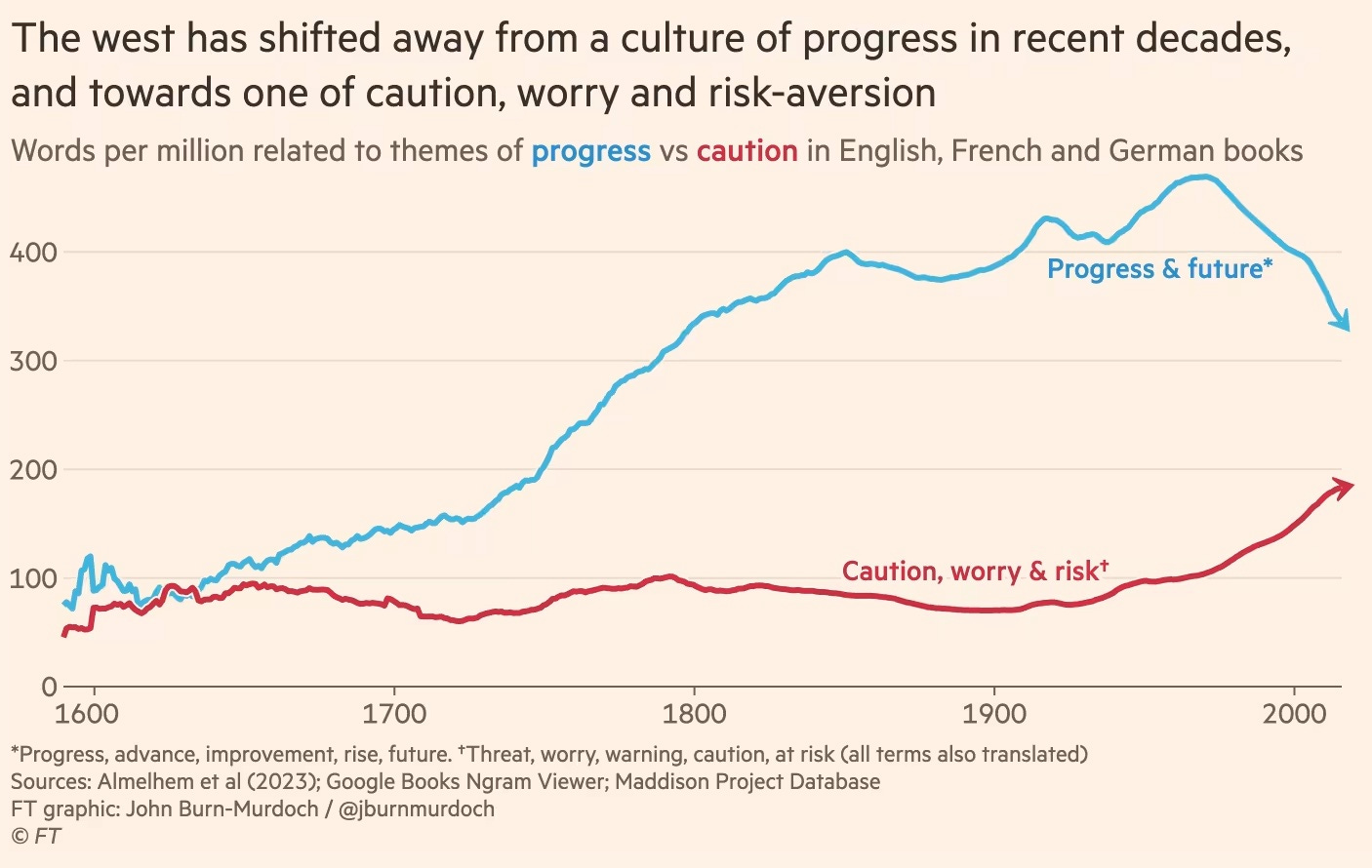

Writing for the Financial Times on January 4, 2024, John Burn-Murdoch took up this suggestion when asking Is the west talking itself into decline? He used Google Ngram to compare progress-oriented words in English and Spanish texts since 1600; the patterns track their differences in GDP and in both cases the change in language occurs before the change in GDP. Suggestive evidence, indeed, but more disturbing is his analysis of modern language usage comparing progress language with caution-risk language in English, French, and German texts:

"Extending the same analysis to the present, a striking picture emerges: over the past 60 years the west has begun to shift away from the culture of progress, and towards one of caution, worry and risk-aversion, with economic growth slowing over the same period. The frequency of terms related to progress, improvement and the future has dropped by about 25 per cent since the 1960s, while those related to threats, risks and worries have become several times more common."

Without succumbing to Whig history, we can celebrate the extent to which progress is possible and science (both propositional knowledge and useful knowledge) leads to human betterment, broadly understood to include our natural environment as well as our built environment, to create a culture and mindset of growth and reject zero-sum thinking. Communities of writers at Works In Progress, Roots of Progress, Human Progress, and the Institute for Progress are reinvigorating this mindset, culture, and language of knowledge creation and sharing, for the use and benefit of humankind. As Burn-Murdoch said in the FT, the “challenges facing the modern world will be solved by more focus on progress, not less.”

I am sure that you already aware of this (but your readers may not be), but there are many other books on progress other than Mokyr's and Landes' books.

Here is a list of the books that I think are the best:

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/the-9-essentials-for-progress-studies

Here is a link to many summaries of books on progress-related topics (from my online library of book summaries):

https://techratchet.com/industrial-revolution-learning-path/

https://techratchet.com/why-did-europe-get-rich-first-learning-path/

M