ShackledAI

What form should additional regulation of AI, if any, take?

Today OpenAI's CEO Sam Altman testified to the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee Hearing on Privacy, Technology, and the Law. In his remarks Altman expressed justifiable optimism and caution with respect to the creation and use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) generally and such large language models (LLMs) specifically.

OpenAI was founded on the belief that artificial intelligence has the potential to improve nearly every aspect of our lives, but also that it creates serious risks that we have to work together to manage ... We are working to build tools that could one day help us address some of humanity's biggest challenges, like climate change and curing cancer. ... however, we think that regulatory intervention by governments will be critical to mitigate the risks of increasingly powerful models.

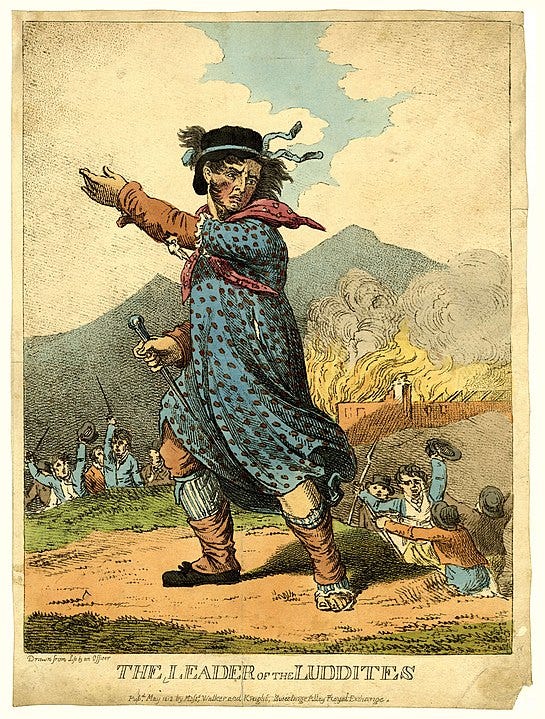

Both optimism and caution are justifiable when learning how to interact with, use, and live with new technologies with unprecedented capabilities. As ChatGPT has demonstrated in its short six-month public life, technologies like generative AI and LLMs have already increased our productivity in a range of activities. At this point those activities are often mundane, like crafting a good email message or curating a long weekend itinerary, and increasingly these models will be able to craft more sophisticated content and provide deeper analysis in contexts ranging from legal briefs to medical questions and beyond. As they grow more sophisticated they will change the employment landscape, although as the Luddites learned with mechanized looms, technology well-used is more often a complement to labor than it is a substitute. This complementarity is a foundation of the increased productivity we experience from new technologies and from interacting with them in new and creative ways. The potential is enormous.

Increased sophistication of capabilities can often lead to using new technologies to do harmful things, with harms ranging from students lazily using AI tools to do their assignments for them to creating convincing deepfakes of peoples' images and voices. Thus it has ever been, including myriad doomsday predictions about how the printing press would destroy society after Gutenberg's invention of movable type in 1440.

We’re all aware of the digital utopians and dystopians, the prophets and fantasists. Experts issue warnings. Regulators advance reforms. Right now we’re in a doom phase: The internet threatens everything from jobs to privacy to free will. We should indeed be thinking about these things. A swelling legion of academic centers and private think tanks does nothing but. Novels such as Tim Maughan’s Infinite Detail and Robert Harris’s The Second Sleep stir the imagination. But as the example of Gutenberg’s invention suggests, it’s easy to forget how unforeseeable (and never-ending) the “unforeseeable” really is. When it comes to those who make predictions about the internet, the judgment of history is unlikely to be: They got it right.

We do certainly seem to be on the verge of a new era. Today's Senate hearing arises in this context – what "should we do" about generative AI and its growing capabilities to create benefit and harm? My taxonomy for these responses is a continuum, from "AI could destroy humanity" at one end to "AI is human created and not a threat" at the other, with various viewpoints in between.

Policymakers naturally lean toward regulation, being generally inclined to "do something" to regulate AI. But how do we create regulatory institutions that provide "sensible safeguards and accountability" (as Senator Blumenthal said in the hearing's introduction) and do not make the mistake of a regulatory framework that stifles innovation and removes the potential benefits as a consequence of avoiding the harms? That's always a difficult bullseye to hit.

In his testimony, Altman stated his support of regulation, "I do think some regulation would be quite wise on this topic", that could take the form of licensing of AI companies as well as testing requirements. Debates on the wisdom and the form of such regulation will rage, but for now, I'd like to highlight one important political economy analysis of Altman's willingness to welcome regulation. Firms can, and often do, support regulation because it has the effect of raising rivals' costs.

The issue of raising rivals' costs arises in the economics literature in consideration of antitrust cases and nonprice competition. One of the most influential models of raising rivals' costs is in Salop and Scheffman (AER 1983), where a larger or early entrant/first mover firm can take nonprice actions that act as inducements to exit to existing competitors or entry barriers to potential competitors.

To a predator, raising rivals' costs has obvious advantages over predatory pricing. It is better to compete against high-cost firms than low-cost ones. Thus, raising rivals' costs can be profitable even if the rival does not exit from the market. Nor is it necessary to sacrifice profits in the short run for "speculative and indeterminate" profits in the long run. A higher-cost rival quickly reduces output, allowing the predator to immediately raise price or market share. Third, unlike classical predatory pricing, cost-increasing strategies do not require a "deeper pocket" or superior access to financial resources. In contrast to pricing conduct, where the large predator loses money in the short run faster than its smaller "victim," it may be relatively inexpensive for a dominant firm to raise rivals' costs substantially. For example, a mandatory product standard may exclude rivals while being virtually costless to the predator. (p. 267)

Regulation is often more costly for smaller firms or for newer entrants or potential entrants. Granitz and Klein (JLE 1996) examine Standard Oil's business conduct in the 1870s as a strategy of raising rivals' costs. Anton and Yao (Antitrust Law Journal 1995) examine how industry standard-setting organizations can make standards decisions that amount to raising rivals' costs in high tech industries. Rubinfeld and Maness (2005) show how patents can be used strategically to raise rivals' costs. From a political economy perspective, then, firms have incentives to argue for regulation in their industry, particularly if they have achieved substantial market share or are an early or first mover. That describes OpenAI.

Does it matter that OpenAI is a nonprofit organization? They are a nonprofit with a considerable financial relationship with a for-profit company (Microsoft). They may genuinely believe in the role of regulation in AI. Even if OpenAI's objective function is not profit maximization, they may still want to maximize their market share, which would mean they have an incentive to recommend regulation that includes requirements for testing and verification they are already doing, which would reduce competition and reduce threat to their market share.

The raising rivals' costs dimension makes it all the more important to think through the array of implications of different regulatory approaches. We want to draw on the insights of early generative AI developers like OpenAI but without raising their rivals' costs. The "doomer" perspective runs the risk of too-stringent restrictions and responding to what amounts to a moral panic. What's a reasonable approach, especially when so many people have so many different ideas about the right way to proceed?

My perspective on this question has three points: the benefits outweigh the risks so we should focus on low-cost risk mitigation policy approaches, industry self-governance and an expectation of public transparency should be a primary pillar, and we should look first at how existing common law and consumer protection regulation already address generative AI risks. In conversation with Russ Roberts at EconTalk on Monday, Tyler Cowen essentially articulated my position, elaborating on the existing and potential benefits (e.g., at around 10 minutes he discusses using generative AI for medical diagnostics in populations with limited medical care). Later in the discussion they delve into the risks and discuss how these risks have recurred in human history with technology. At about 39 minutes Tyler makes the crucial point that preventing technological change has its own risks:

There are very serious risks ... our reaction to an event can be worse than the event itself, even if the event involves some very high costs.

This point also illustrates one of the important insights from the 19th century French economic journalist Frédéric Bastiat on the seen and the unseen. If members of Congress impose additional generative AI regulations that stifle innovation, what's unseen is the productivity, health, human flourishing benefits that would have been created but were never allowed to exist.

In particular, at about 44 minutes Tyler raises some of the important economic, epistemic, and cognitive justifications for rejecting the doom message and thinking through the regulatory approaches:

Now, if you ask what do I think of the regulatory process, who or what exactly in government? And, I do mean exactly: I would like to hear much more on this question from the doomsters. Who is capable of making the problem better rather than worse?

Is it the FTC [Federal Trade Commission]? In my opinion, no. All their doomsaying about concentration in social media clearly has been shown to be wrong. And they're still at it, trying to take down those companies.

One Biden proposal gave some authority to the Commerce Department. They may be good in the sense they might not do that much, but their expertise in this area seems to me highly limited. They tend to be quite mercantilist, looking for national champions. That might be good if you're relatively positive on these developments, but it doesn't actually seem like a good match if something substantive needed to be done.

... and then at about 50 minutes he addresses the epistemic and cognitive characteristics of "intelligence" and knowledge that both he and I think will limit the risks associated with generative AI:

Everything is coded into a program in one worldview. In what you might call the Austrian Economics worldview, decentralized and often inarticulable knowledge, as outlined by Michael Polanyi, is critically important for just about everything that happens. GPT models do not in any direct way access that. They're not trained on it.

There is a sense in which they digest a version of the outputs from the process based on decentralized and inarticulable knowledge. So, they have a good deal of cognitive oomph.

But, the notion of AGI, to me, is not entirely well-defined. Getting back to this point of multi-dimensionality, it's not just prudence or wisdom or judgment, but even very crude notions. How you realize your intelligence through physical actions in the world in a way that, say, LeBron James does. A phenomenally smart human being in both the intellectual sense, and also the physical sense, and integrating the two. That's yet another dimension we haven't considered.

So, this idea when people say, 'Oh, AGI is X number of years away,' that doesn't make sense to me. If your notion of AGI is a particular kind of smarts, you could argue we're already there. I mean, GPT-4 has been measured at an IQ of 130. GRE [Graduate Record Examination] scores very high, sometimes close or at perfect. But it's a device--and, again, we need to keep the broader perspective. And, I'm hoping that you, in particular, with your training in Hayek, Smith, don't let the doomers sell you the emotion.

The correct attitude here is to take lessons from history. History is one form of knowledge. It is not always generalizable, but there's a lot you can learn from it.

My second and third point dovetail with an outstanding post from longtime technology policy analyst Adam Thierer. Adam has long argued that overly precautionary approaches to technology regulation stifle innovation that on balance creates substantially more benefits than risks, and that as our relationship with technology evolves we generate new ways of managing those risks. And he cites extensive data and research, so his post is informative and provides you with extensive resources to examine and consider.

Adam writes his recommended Senate testimony for Sam Altman in the context of the political environment surrounding technology regulation:

If this hearing plays out like many other recent tech policy hearings, the session could be heavy on AI “doomerism” (i.e., dystopian rhetoric and pessimistic forecasts) and be accompanied by the usual grievance politics about “Big Tech” more generally. Congressional hearings on tech policy matters have become increasingly angry affairs, as “outraged congressional members raise their voices and wag their fingers at cowed tech executives” to play to the cameras and their political bases. ... Lawmakers need to realize that we are living through a profoundly important moment and one that the United States must be prepared for if the nation hopes to continue its technology leadership role globally.

Here’s what Sam Altman should say to set the right tone for this and future AI policy hearings.

I strongly recommend reading Adam's shadow speech in its entirety, which he organizes around three general recommendations:

Avoid overly burdensome technology regulations that undermine generative AI's benefits

Extensive state capacity for generative AI oversight already exists, including both common law and existing consumer protection laws

Any remaining policy gaps should be addressed using flexible approaches that are risk-based and focus on outcomes rather than on controlling inputs or processes

The Senate Subcommittee would do well to consider not just the risks of generative AI, but also the risks of regulation that reduces innovation, that raises rivals' costs, and that does not leave room for using our existing common law and regulatory mechanisms that can protect consumers and create conditions for future flourishing.

Excellent. Thanks for the pointer to Thierer.

I suspect the issue is partly that there aren't many AIs yet, and some on the right are concerned they are woke. A new page makes the point that they will be embedded in the office suites of Microsoft and Google soon and nudge most of the words written on the planet, which suggests an understandable concern, but that market competition can address that if 3rd parties provide AIs with different biases:

http://PreventBigBrother.com

I suggests the need for something like Section 230 to prevent liability issues from undermining the rise of AI, and argues against government control of AI as being akin to government control of speech that we have a 1st amendment to protect against. While it protects the rights of listeners to hear speech, its unclear if it'll protect the creation of that speech they wish to hear by a machine rather than a human.