Market Design and Negative Prices

What do negative prices in power markets communicate?

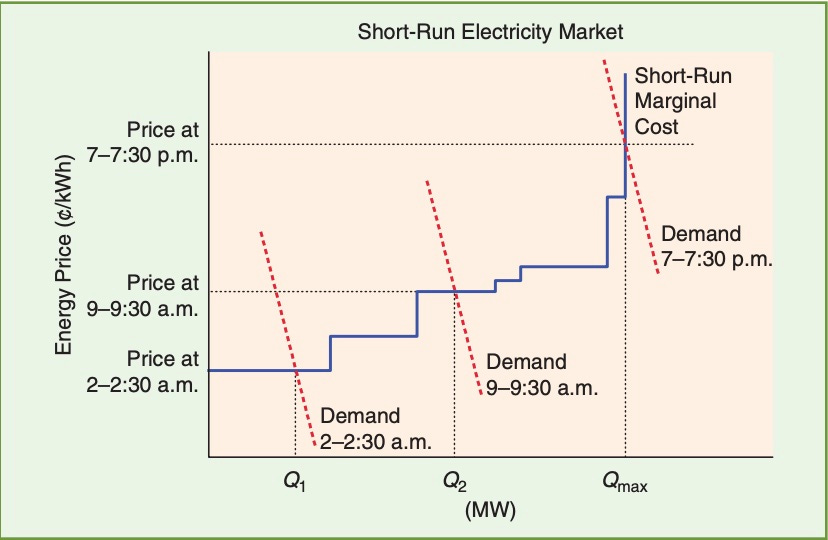

Source: Hogan (2019)

Power markets are coming in for a lot of criticism these days, a good deal of it justified. As I’ve argued here before, organized power markets are administrative constructs that are grounded in some solid market theory and principles, but they have both institutional design features and governance problems that make them less effective than they could be at dynamic value creation.

Yes, they have reduced costs, improved capacity utilization, decreased wasted resources, and induced innovative investments compared to vertically-integrated structures (as Steve Cicala ably demonstrated in the work I cited in my March post on vertical integration), but whether it's long-run resource adequacy, problems of price integrity and risk taking given out-of-market government interventions, integrating low-carbon low marginal cost resources, or RTO governance that creates perverse incentives, organized power markets have room for improvement.

One useful way to think about improving RTO and power market institutions is by asking how well they incorporate foundational economic principles and allow for meaningful, transparent, accurate price discovery as technologies and conditions change over time. A lot of scholars have spilled a lot of ink on this question over the past 30 years, so to cut to the chase I’m going to recommend a recent analytical opinion piece by William Hogan, one of the preeminent electricity market design researchers (Hogan, William W. Market design practices: Which ones are best?[in my view]. IEEE Power and Energy Magazine 17, no. 1 (2019): 100-104) Hogan concisely summarizes the combined engineering and economic logic behind bid-based security-constrained economic dispatch and the focus on day-ahead and day-of spot markets, to complement other long-term contracting arrangements between generators and buyers (either regulated utilities or independent retail energy providers). This institutional arrangement could yield both static efficiency and dynamic efficiency through robust investment and innovation incentives presented by the ability to sell at higher prices in higher-demand periods.

…the increasing short-run marginal cost of generation defined the dispatch stack or supply curve. Thermal efficiencies and fuel costs were the primary sources of short-run generation cost differences. The introduction of markets added the demand perspective, where lower prices induced higher loads. As demand shifted over the day, prices would rise and fall. The rents earned by generators, in the periods when prices were higher than dispatch costs, would provide the contribution for covering the cost of investment.

Theory and implementation always differ in something as complex as the cyber-physical-social systems that are modern markets. Hogan notes that “[t]he practical application of the basic principles has been highly successful but not always perfect. A major problem occurred with implementation details that tended to depress the spot energy price, particularly during periods of constrained capacity.” Politically expedient price caps give comfort to politicians that voters will not experience price volatility and generators will not profit from exercising market power, but they undermine price discovery processes and make markets work more poorly.

Let’s apply these principles to the phenomenon of negative market-clearing prices. Are negative prices in power markets inherently a problem indicating flawed market institutions? Not really, but depending on what's causing the negative prices, they can indicate that market institutions are not adapting to changes in the underlying technologies, in economic patterns, or in government policies.

Negative prices mean a supplier will pay someone to take their power. Negative prices occur in markets with tightly-coupled vertical supply chains, meaning for the most part that there's a physical interdependency outside of the scope of the market that affects whether or not transactions can be fulfilled. Not surprisingly, then, they tend to happen more in markets that involve specific timing and physical infrastructure for delivery of the transacted product/service. And even though they have occurred in previous decades when the dominant generation resources were thermal (coal and natural gas), nuclear, and hydro, they are occurring even more with the increase of wind and solar resources in the generation mix.

Regardless of the technology of the resource, negative market-clearing prices arise for three reasons: startup costs and timing mismatches, congestion and timing mismatches, and government policies. Large-scale generation technologies like nuclear are very, very costly to start up (and big coal plants are also costly, but less so). They can adjust their production to some extent, but it's limited. If the plant is running and there's not enough demand to take all of the power at that time, the generator would be willing to pay buyers to increase their quantity demanded so that they can avoid having to incur their startup cost again.

The second reason for negative market-clearing prices, transmission congestion, arises because in a transmission network, when generators invest in new units in places where there wasn't generation before, the transportation network doesn't exist to connect sellers in that location to buyers in other locations. This congestion problem is one driver of negative prices in systems with increasing wind generation, because wind turbines are generally built in places with lower populations, to sell to buyers in more densely-populated locations. It's one of the biggest challenge of capital-intensive, high fixed cost infrastructure industries where the infrastructure has a 30+ year useful life – once you build the network it's a sunk cost, and transmission is expensive and takes a long time to permit and build.

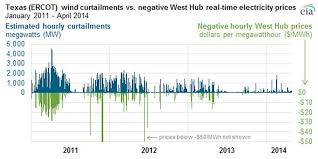

The experience in Texas illustrates this second cause of negative prices. Wind turbine investment increased in West Texas starting in 2007; with demand in the cities east of there, transmission connections from these new wind farms were sparse and negative prices ensued due to transmission congestion. Texas policy makers and regulators took those negative prices as (opportunity cost) signals of where the highest marginal value would come from additional transmission investment. Their CREZ transmission investments in the mid-2010s reduced the incidence of negative prices.

Source: Energy Information Administration

In the case of wind, what really amplifies the incentive to offer in at negative prices is not just the generation pocket congestion, but also the government subsidy in the form of the production tax credit (PTC) paid to wind resource owners. Wind companies receive the PTC based on actual generation, so they are willing to pay up to the amount of the PTC in pre-tax income to continue generating and not curtail production. Note that not all periods with negative offers lead to negative prices – the way security-constrained economic dispatch works means that when wind power is abundant and when demand is sufficient, wind generators may still submit low or negative offers to make sure that they get chosen and get dispatched, even if there's enough demand that the market-clearing price is positive. In those periods, and assuming that all resources are being bid in at or close to their marginal cost, the distortion from the PTC is minimal because those units are not the marginal unit setting the market-clearing price.

The PTC subsidy has introduced a distortion to power markets by amplifying the phenomenon of negative market-clearing prices. Given the decrease in the cost of wind generation to the point that it's competitive with other resources, the PTC was due to expire in 2020, but it has been renewed, again and again, most recently in the Inflation Reduction Act (2022). It's a subsidy without economic merit given how mature wind technologies are now – they don't need the PTC to induce them to make low enough offers to get dispatched – and if you compare the PTC to the counterfactual with no PTC, it represents a transfer of surplus from taxpayers to wind generators.

Adapting market design to the situation with some resources receiving subsidies and some not is one of the biggest challenge facing power markets today. The subsidies muddy price formation and make prices less meaningful and less informative than they would be otherwise. They also can harm reliability to the extent that lower (and negative) prices reduce investment incentives in a dependable generation portfolio. Mays and Jenkins (Mays, Jacob, and Jesse D. Jenkins. Financial Risk and Resource Adequacy in Markets with High Renewable Penetration. IEEE Transactions on Energy Markets, Policy and Regulation (2023)) characterize this argument as

Due to price and offer caps used to mitigate market power, as well as the difficulty of pricing intertemporal constraints and certain actions taken by system operators to guarantee reliability, prices in energy markets are suppressed below the level needed to support an efficient capacity mix [16]. Growth of variable renewables could exacerbate this suppression, leading to greater reliance on supplementary revenue streams to ensure resource adequacy [14]. Existing resource adequacy constructs may not be equipped to the task of supporting a transition because they preferentially support financing of technologies with higher marginal costs [11], do not adequately address the need for flexibility [17], and may be more subject than short-term markets to pressures of deregulatory capture [18], through which incumbents can steer market rules to their own advantage [19]. Designing resource adequacy mechanisms that resolve these issues without fixing the underlying flaws in short term price formation amounts to a new form of centrally organized integrated resource planning. In this context, skepticism about the future viability of markets equates to a belief that systems will fail to address underlying flaws in short-term price formation.

One oft-cited reason for these interventions to manipulate the short-term price formation process is that demand is unresponsive, or price inelastic. Using digitization to automate demand and make it price responsive would attenuate some of the structural problems that lead to both volatile and negative prices (although in the case of the PTC it would still be a transfer from taxpayers to generators and to the buyers who get paid to use their power), and in general would enable markets to work better. Again returning to economic principles, Hogan makes the argument for clear, accurate price signals arising from price discovery (supply and demand).

Another implicit assumption of the flawed argument is that demand participation can be managed without efficient pricing mechanisms. Under the current supply configuration with large thermal generators, it is possible to imagine centralized control without the benefits of spot prices. … Moving to a greater reliance on distributed resources (many and small) and demand participators (many and small) leads inexorably to a greater need to have real-time spot prices that send the right price signals. The central control of distributed resources would not be feasible, and prices must provide the needed incentives. Failure to provide the right price signals will lead to distributed decisions that would undermine efficient operations.

Note the language that Mays and Jenkins used: "Designing resource adequacy mechanisms that resolve these issues without fixing the underlying flaws in short term price formation amounts to a new form of centrally organized integrated resource planning." Combine that with Hogan's observation about the essential role of price discovery in an increasingly distributed system. Central planning as currently implemented at RTOs that operate power markets overlooks that fundamental role of price discovery for coordination in a highly distributed complex system, and will lead to inferior outcomes. A price is a signal wrapped in an incentive, including when that price is negative.

Prices tell us important things, like where transmission investment would be most valuable, or where start up costs are a problem in a generation pocket, or where subsidies do distort market-clearing prices. They tell us when and where power is relatively scarce and relatively more valuable. Devising administrative mechanisms to mute prices in the name of long-term resource adequacy replaces flawed central planning for the better (although not perfect, nothing is perfect) decentralized price mechanism.