Economics is the analysis of how people coordinate their actions and plans around the use and creation of resources. Defining economics this way focuses our attention on the crucial role that institutions, the “rules of the game”, play in structuring the environments in which we make decisions. One of the essential ways we coordinate is through market mechanisms that form the nervous system of our social order and serve as knowledge ecosystems.

Markets Are Knowledge Ecosystems

The integrity of price signals is crucial for markets to fulfill this nervous system role, and when critiquing specific market institutions it's important to keep price signal integrity in mind and use it as a metric to evaluate how well a market's context and rules serve its users. In other words, market questions are institutional questions. Market processes arise and occur within institutional contexts, not in the sterile environment presented in most introductory economics textbooks. The legal environment, the economic context, the social environment, and the technology set all set the stage for the specific rules that govern any particular market and its operations.

All markets, every single market in which we interact (and we interact in many on a daily basis), are a combination of practices that emerge over time and place with specifically-designed rules. All markets are partly emergent and partly designed. All markets are constructs to a degree; construction is a continuum.

That general preface is where I want to build on my previous newsletter where I discussed FERC Commissioner Mark Christie's Energy Law Journal article, focusing on his flawed arguments for eliminating uniform price auctions in electricity markets.

Note also a recent Heatmap News article from Matthew Zeitlin interviewing Commissioner Christie about his article. Here I focus on the second claim he makes, that electricity markets are not "true" markets:

This article uses the short-hand term "markets" for these administrative constructs known as RTO power markets, but the use of the term "markets" does not change the assertion herein that these are administrative constructs with some market characteristics, not true markets. (p. 4 fn. 9)

Christie does not define his benchmark of “true” markets in the article. This false dichotomy of “markets: true and false” (that's a Hayek Easter egg for you) demonstrates a lack of understanding of markets, how they emerge, how they evolve, and how they are constituted. All markets have institutional frameworks, ranging from common law rules against force and fraud to regulatorily-defined market designs. All markets are constructs to a degree.

Two ideas are in play here: the more general concept of what constitutes a market, and the specific example of electricity markets, particularly organized wholesale power markets. The general question of what constitutes a market has a long history, going back before Adam Smith in 1776. Some of the most interesting work in this area comes from experimental economist Bart Wilson, who uses laboratory experiments to create environments that reflect characteristics that led to the emergence of impersonal exchange among strangers (e.g., Kimbrough, Smith, and Wilson, Building a Market: From Personal to Impersonal Exchange (2007)). Market processes are the processes of mutually-beneficial exchange between parties, and if you want a definition of a “true” market, that's it. But it's a very general conceptual definition, probably not the operationalizable definition that Commissioner Christie has in mind.

Even that stylized experimental bilateral exchange between strangers requires an institutional context, and if you start at a hypothetical state of nature, the process of exchange creates the institutional context (see also James Buchanan, Order Defined in the Process of Its Emergence (1982)). The first few times, people take a risk reaching out to a stranger to trade, probably starting from whatever has worked in exchanges within their personal spheres. With repetition (with each other and with other strangers) they learn what works well for both parties. Those emergent best practices become trading norms. If there are conflicts they negotiate through them, or maybe pull in a third party to adjudicate the disagreement. Over time and with repetition, the norms that “work” stay in play and those that aren't as mutually satisfactory to different parties disappear. In this very important, very human experience-grounded sense, market rules are emergent institutions arising out of custom, practice, and repetition with different combinations of parties.

As communities, societies, nation-states themselves emerge, these customs get codified into formal law; this is the bottom-up process by which the English common law evolved, for example. Those third party adjudicators become judges and courts. The institutional context for markets becomes more structured, more formal. Historically, it's in this institutional context that formal financial markets emerged in the 17th century. Notice the institutional layers, the polycentricity of the institutional framework – financial market operators deliberately design a set of rules governing their markets, which operate within the broader legal context as well as the broader social and technological context. Again the same feedback effects apply, though; if those market operators have rules that don't “work” for both sides of trades, those market operators don't profit, which gives them an incentive to revise their rules, change the services they offer, and so on. This process of institutional change motivated by the mutual profit motives of buyer, seller, and platform operator characterizes the past four centuries of financial market evolution. But even in more prosaic forms of markets like retail shops with posted-price market designs, the same dynamic has driven responsiveness and institutional change.

Source: Financial History of the Dutch Republic, Wikipedia

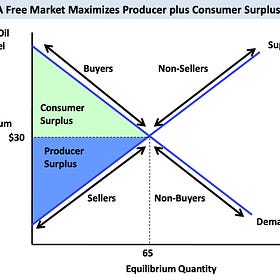

When Commissioner Christie invokes “true” markets, that's what I have in mind, although I don't know what he has in mind. Perhaps he has in mind the “Econ 101” notion of “perfect competition” with its assumptions of many participants, full information, free entry and exit, and so on. While useful as a stylized first step to understanding and providing some policy guidance for the benefits of lowering entry and exit barriers, this static classroom model lacks all of the institutional context that is essential for creating “true” markets in reality. It's a starting point, not an end state.

The difficulty arises in the murky area of adding the administrative state layer to this polycentric institutional framework. In the stylized institutional stack of social, legal, and organization-specific norms/rules, the regulation and discipline of bad behavior by either buyer or seller or platform operator arises out of the organizational sanction, the legal sanction, and/or the reputation mechanisms of social norms. For various historical and theoretical reasons that deserve their own separate treatment, administrative regulation has supplanted much of the regulation that occurred through the other layers in the institutional stack. That's the case in organized financial markets, in public utilities, and in the more recent evolution of organized wholesale power markets.

From their origins in the 1990s organized wholesale power markets have been regulatory constructs, as Christie describes, selectively, in his article (pp. 12-16). But they are regulatory constructs grounded in two other important dimensions that reflect more of the historical emergence and evolution of dynamic, organic markets. First, their designs incorporate and build on centuries, and yes I do mean centuries, of market customs, practices, and rules that have stood the test of time and served their parties well in a wide variety of exchange contexts. This institutional evolution is why the “emergent order-designed order” dichotomy is at least partly false – many of the design elements of wholesale power markets have emerged over four centuries of organized markets and have been codified into business best practice, into formal legal requirements, or into administrative regulations. In the case of electric power it's all three. But not all design elements in wholesale power markets are these salutary exchange practices that have stood the test of time (more on this shortly).

A second dimension of wholesale power market design is the extent to which it is a function of the 1990s technology environment, particularly the set of generation technologies and the expectation of what kinds of parties would be doing the generating. The 1990s technology landscape involved nuclear, coal, and natural gas generation, at large scales but also at diversifying scales as smaller combined-cycle gas turbines reduced economies of scale in generation. Wholesale power market designs were intended to get the most bang for the buck out of these resources, increasing capacity utilization and lowering generation costs, while also providing dynamic investment incentives to guide longer-term decisions toward greater dynamic efficiency. In achieving those objectives they have been broadly successful, accomplishments that Commissioner Christie seems to discount.

These 1990s era market designs have not evolved beneficially as the technology context and the policy landscape have changed, and here I agree broadly with Christie's point. The institutional changes that have occurred through top-down regulatory channels have not performed well in delivering mutual benefit to buyers and sellers while enabling reliability and the integration of diverse generation technologies with different characteristics. In this section of his article he directs his criticism at the development of capacity mechanisms since 2005. Capacity mechanisms provide a second payment to generators in addition to their payments in day ahead, hourly, etc. energy markets, a payment for having available generating capacity. Typically these are implemented through procurement auctions in which the Regional Transmission Organization that operates the power markets takes its reliability planning forecasts and turns them into an (inelastic) demand for generating capacity. Note that by regulatory design the RTO is the monopsonist in this “market”. The idea here is to engineer a framework in which generators have incentives to invest in enough capacity to ensure adequate resources to meet their reliability requirements; if this idea is new to you I recommend this capacity mechanism primer from Penn State University (quite possibly the product of my friend Seth Blumsack).

Christie is absolutely correct that capacity mechanisms are administrative constructs, but his analysis is incomplete because he ignores the regulatory flaws that created the environment in which regulators and RTOs have implemented capacity mechanisms. As accurately described in the Penn State primer, the regulatory context for today's wholesale markets includes (1) an installed capacity requirement dating back to the 1960s, (2) price caps to insulate retail customers from price volatility, and (3) inelastic demand and a mismatch between retail prices and costs because of retail rate regulation. All three of these regulations should be open for reevaluation, amendment, or elimination given the changes we are experiencing in technologies and in consumer expectations.

In his article Christie does not acknowledge in particular the role that price caps have played in creating a rationale for capacity mechanisms. All wholesale markets have price caps, which truncate the producer surplus that generators can earn. Some of them have pretty low price caps, and the ones with the lowest price caps have the most elaborate capacity mechanisms. Those high-value periods are important for inducing generation investment, and by undercutting them price caps make generators less economically viable. Capacity mechanisms serve as a regulatory band-aid on top of the regulatory cut of price caps, a regulation to ameliorate the negative effects of a different regulation. And, like the general market designs, they are predicated on a very specific set of generation technologies, particularly gas generators circa 2005, while the supply portfolio has changed considerably in the ensuing 18 years.

The putative justification for wholesale price caps is to protect retail customer affordability. Christie and too many others who work in electricity policy are too committed to thinking in terms of regulation and regulated prices as a necessary way to ensure affordability for customers. This institutional framework is particularly a mismatch in a technology and policy context in which more residential customers have the digitization that makes them more flexible and more responsive while also owning lower-carbon supply resources like EVs and batteries. A more imaginative and potentially more beneficial way to enable affordability is to be explicit about price insurance as an additional service instead of baking it in to regulated rates as a mandatory requirement. If a residential customer has a price insurance contract with their retailer, then any wholesale price spikes that the retailer wants to pass through will be limited, as will customer bill impact. That would be a cheaper insurance policy than building expensive generation capacity that will never be used, which is what capacity mechanisms induce.

Yes, capacity mechanisms are an administrative construct and not a market. There are good substitutes for them in the form of insurance products and financial instruments, and good reasons to eliminate them. Let’s do so on firm theoretical foundations about what markets are and how they are constituted.

Great job explaining the evolution of markets and their relationship with institutions. This is a much better way of approaching economics compared to the fantasy perfect competition model (which should only be introduced considerably later).

I'm going to have to listen again but what a brilliant idea of I understood correctly. Going to let it simmer in sub then look again tomorrow. Regardless, something awesome you have seeded.