Quarantining the Monopoly: A Conversation with Doug Lewin

Technology has changed a lot in electricity and beyond, and regulation should too

I was thrilled to join Doug Lewin on the Energy Capital Podcast for a quick tour through a century of electricity economics and the design choices now facing us. The conversation moved from Edison and Insull in the 1880s to digitalization and distributed energy resources today, and it asks a straightforward question with complicated implications: what belongs inside a regulated monopoly, and where should competitive price discovery do the work regulation cannot? The episode runs in two parts; part one is out now, and part two, on data centers and competition, arrives next week. This post distills my perspective from the first part of our conversation.

I came to this industry as an economist who loves history (indeed, as an economic historian) and technology. That history matters. Late-nineteenth-century electrification was a hotbed of invention and business model experimentation. Edison envisioned electricity as an engineered, integrated system and, with his team, pushed from fuel to the filament in the light bulb. Samuel Insull operationalized that vision in Chicago with organizational acumen and an eye for finance. Cities granted (multiple overlapping) franchises, reformers worried about corruption, and investor-owned utilities sought stability. Rate-of-return (ROR) regulation met all these needs at once: it made capital formation predictable, it rewarded large, long-lived assets, and it locked in a structure that delivered universal service. The economics were compelling. Big plants running many hours cut average costs, and serving lighting, industry, and traction using one set of assets owned by a single firm spread fixed costs across more uses. ROR regulation also served the interests of the Progressive Era reformers worried about big business. On its own terms, the model worked; the United States became an electrified nation.

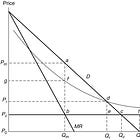

This success also created habits. ROR regulation pays for capital and allows recovery plus a benchmark return. That feature built the network; it also formed a capital bias (aka the Averch-Johnson effect). When the toolkit contains mostly “iron in the ground,” the reflex is to build more iron. The bias becomes a bug when technology changes the feasible set.

Technology did change it, first in generation starting in the 1980s, then in the connective tissue of the system via digitalization over the past decade. The combined-cycle gas turbine in the 1980s ended the presumption of pervasive economies of scale, that generation must be enormous to be efficient. Smaller, modular plants with different cost structures could compete with coal, hydro, and nuclear when market rules allowed prices to communicate value across time and place. Digital technologies then lowered transaction costs up and down the system. Sensors in substations, smarter protection schemes, telemetry at the grid edge, and interoperable standards made it possible to coordinate many owners and devices without a single vertically integrated firm knitting every piece together. This combination of modular generation and digital coordination makes the twentieth-century business model feel and act creaky. The economics now point to a different boundary for the monopoly.

This argument leads to a simple design principle: quarantine the monopoly. Keep the regulated footprint where network economics and economies of scale and scope still dominate—transmission and distribution wires, operated as a neutral platform with obligations for safety, reliability, and universal access. Allow competition everywhere else, including services that help the wires perform better. Markets excel at price discovery; monopolies do not. Regulation can set objectives (although imperfectly) and guardrails, but it cannot replicate the information that emerges when many actors pursue opportunities and bear the consequences of their choices.

Texas offers a vivid case study in why this matters. In ERCOT’s wholesale market, prices move, sometimes sharply. This volatility often attracts criticism, yet it is information, not failure. Prices tell us when supply is scarce, when flexibility has value, and where capital should flow. Arbitrage, another frequent target of criticism, performs quiet coordination. When participants buy low and sell high across hours and locations, they flatten volatility, allocate risk to those willing to bear it, and signal profitable niches for storage, demand response, and fast-ramping generation. The result is a learning system. Investors test theses; some succeed; some fail; customers benefit from the cumulative discipline of entry and exit. Risk sits with private capital rather than captive ratepayers. This arrangement does not promise smoothness; it does create adaptation.

If wholesale and retail markets in places like Texas demonstrate the virtues of discovery, the distribution system there and elsewhere shows where we have more work to do. Distribution utilities still default to concrete and copper because ROR regulation pays them for those inputs and not reliably for outcomes. For example, a feeder overload appears; a substation upgrade moves onto a capital plan; rate base grows (although slowly given the supply chain backlog for transformers). Yet managed EV charging can reshape local load shapes; behind-the-meter storage can shave peaks; targeted efficiency and flexible industrial processes can remove the need for steel altogether, and all of that flexibility can be automated and implemented thanks to digital technologies. These resources rarely receive a chance to compete against traditional upgrades, not because they cannot deliver reliability, but because institutions do not give them an opportunity to do so.

This gap is solvable. Performance-based regulation can align earnings with defined outcomes—reliability improvements, cost containment, interconnection speed—rather than with spending alone. So-called "non-wires alternatives" can be integrated into planning by specifying location-specific needs and running competitive procurements in which aggregated distributed resources bid to meet those needs. Savings relative to the “wires-only” counterfactual can be shared between utilities and customers, ensuring utilities remain indifferent, or even positively inclined, when a lower-cost portfolio beats a capital project. Data access, standardized telemetry, and transparent interconnection queues form the plumbing that allows this competition to function. This institutional plumbing is dull in description but transformative in effect.

Some people will rightly ask about policy overlays—renewable credits, reliability programs, and the like—and their interaction with price formation in wholesale power markets. The lesson from multi-state markets such as PJM is cautionary: when policies muffle price signals, markets learn the wrong lessons. Texas has made a different policy choice: allow prices to speak and then build guardrails around consumer protection and market integrity. This choice does not settle every argument, but it keeps the communications network of prices intact. This fidelity matters because no planner, however well-intentioned, can know the right portfolio ex ante. Markets do not produce perfection; they produce discovery.

What follows from this analysis is an institutional design recommendation. Preserve the monopoly where the physics of the network requires it. Demand neutrality from the platform. Invite competition everywhere the economics supports it. Pay for performance, not for inputs. Treat volatility as information to be analyzed and managed, not a mistake to be erased. Build institutional plumbing that lets distributed resources solve local problems, and compensate utilities for enabling those solutions rather than for crowding them out.

This moment rewards institutions that learn. Twentieth-century regulatory institutions delivered universal electrification by financing a single, vertically-integrated, capital-intensive architecture. The twenty-first century presents a modular, digital system whose value emerges from coordination across many actors. Quarantining the monopoly is a way to align incentives with that reality, so discovery can do the work bureaucracy cannot.

Lynne, you are a wonderful writer! I haven’t seen such beautiful prose describe our grid conditions since Gretchen Bakke’s treatise a decade ago.

I just covered in my class (https://ESE.lehigh.edu) the work of Tesla and Edison but also of Insull the unsung hero for his commoditization of electricity. It is the reason why electric power and the lack of it separates prosperity and poverty even today. Your proposal to re-examine the future grid for which parts needed to be regulated and which ones thrown out for competition is very good. There are some ticklish areas: GFM vs GFL Inverters for one.

I will forward your Podcast to my students.

Lynne, doesn’t the regulation you describe require knowledge on the part of regulators that they cannot have, per Hayek? And if that is “necessary” because the regulated entity is a monopoly, doesn’t that perpetuate a monopoly that might otherwise lose its monopoly power as conditions change?