Discover more from Knowledge Problem

Subsidies, External Costs, and Deadweight Loss

How do federal subsidies for wind and solar affect wholesale power markets?

Economic analyses of wholesale power markets are important even if you aren't deeply interested in power markets themselves. Power markets are both an application of economic theory and an informative feedback loop to help us identify when the effects of particular regulatory or market institutions are, or are not, what was expected from the application of theory. If you are interested in applied economics you should be interested in power markets. And vice versa.

U.S. federal tax policy toward renewable energy technologies illustrate this point brilliantly, and demonstrates how strong the political dynamics are that often lead to worse outcomes than what economic theory would yield. This topic comes up in the context of my critique of FERC Commissioner Mark Christie's recent Energy Law Journal article, and is the third in my series of analyses. My first post analyzed his misguided criticisms of the use of uniform-price auction design in energy markets, and my second explored the question of what constitutes a market, given his invocation of “true” markets and his largely valid criticisms of administrative capacity mechanisms.

In this, my third and final post on Commissioner Christie's article, I take up his argument that government subsidies distort wholesale power market outcomes, creating deadweight loss and reducing their efficiency/surplus creation in both a static and dynamic sense. He's correct in making that claim, but there's more to the analysis than he provides.

... some resources are almost always going to clear both because they effectively have no marginal costs (although significant upfront capital costs) as well as heavy federal and state subsidies that may allow them to offer at a price of zero or even below. Both these factors give renewables a significant advantage over competitors that have significant marginal costs (but may have lower capital costs). (2023, p. 17)

Federal Tax Policy as Energy Policy

The fact that these subsidies affect outcomes in wholesale power markets is well known and has been for over a decade. The disagreement is on the magnitude of the effects and whether the subsidies are mostly creating deadweight loss/inefficiency or are internalizing an external cost that is not otherwise reflected in markets. In the interest of brevity here I'll focus on federal tax policy; in a later newsletter/post I'll have more to say about state renewable portfolio standards (RPS) and their effects. If you are even remotely interested in federal energy policy and/or tax policy, I strongly – strongly – recommend reading Metcalf (2007) (Metcalf, Gilbert E. “Federal tax policy towards energy.” Tax Policy and the Economy 21 (2007): 145-184), who does a thorough and masterful job of cataloguing energy tax policy's history, details, and impacts on taxpayers. His analysis does not reflect changes since 2007 and in particular does not speak to the tax instruments used in the climate provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act (2022), but it remains an outstanding resource. His catalogue in particular demonstrates how pervasive tax subsidies are and have been for decades in energy, for fossil, nuclear, and renewable technologies.

The federal production tax credit (PTC) for wind power was established in the Energy Policy Act of 1992 (yes, the same legislation that enabled independent power producer and wholesale power market formation). As of 2007,

Section 45 of the IRS code, enacted in the Energy Policy Act of 1992, provided for a production tax credit of 1.5 cents per kWh (indexed) of electricity generated from wind and closed-loop biomass systems. The tax credit has been extended and expanded over time and currently is available for wind, closed-loop biomass, poultry waste, solar, geothermal and other renewable sources at a current rate of 1.9 cents per kWh. Firms may take the credit for ten years. Refined coal is also eligible for a section 45 production credit at the current rate of $5.481 per ton. EPACT added new hydropower and Indian coal with the latter receiving a credit of $1.50 per ton for the first four years and $2.00 per ton for three additional years. (Metcalf 2007, p. 161)

EPACT 1992 also created a production tax credit for nuclear generation of about the same magnitude as the wind PTC. Since 2007 the PTC has been on the verge of expiring multiple times but has always been renewed, most recently in 2021 at 1.8 cents per kWh. The financial impact of the PTC on wind development's return on investment is demonstrated by the variable pattern of wind investments, falling as PTC expiration approaches and then zooming back up once it's renewed. 2022's Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) extends the PTC through 2025 and creates a base level credit and an increased credit amount of up to 2.6 cents per kWh if certain U.S. sourcing and economic development criteria are fulfilled.

The other major federal tax policy affecting wholesale power markets is the investment tax credit (ITC). Established during the oil crisis-ridden 1970s, the ITC took effect in 1978 to provide a then-temporary 10% tax credit to energy investments other than oil and gas. The rationale was to diversify the national energy technology portfolio, largely for national security reasons but also for environmental benefits. The solar (and geothermal) ITC at 10% was made permanent in EPACT 1992, although it has increased and decreased as policy makers tried to induce greater investment, and through that channel induce production cost decreases and increases in solar PV's energy efficiency. As with the PTC, the IRA in 2022 extended the ITC.

What Does Economic Theory Predict Will Happen?

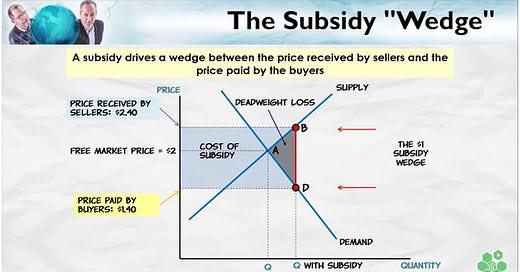

These two different tax credits create different economic incentives, and those incentives are different from a standard textbook treatment of subsidies. The simplest subsidy model involves paying a subsidy $s per unit of output to each supplier, leading to a downward-outward shift in the supply curve and a wedge between the (lower) price consumers pay and the (higher) price sellers receive.

Source: Cowen & Tabarrok, Modern Microeconomics

The PTC/ITC operate very differently because they are technology-specific and are not paid to all suppliers of electricity. In the wind PTC, to be eligible for the credit the generator has to operate and to sell electricity, so in an organized market that generator will submit a low enough offer to make sure it gets dispatched. The pre-subsidy marginal cost (MC) of a wind generator is close to zero, so even before the PTC, the wind unit comes in at the left side of the supply curve, below nuclear, and shifts the supply curve outward. The wedge between what the seller receives and what the buyer pays is not as clear as in the textbook model, so it's harder to interpret the effects of the technology-specific subsidy – what we can say with certainty is that by inducing greater investment in a low-MC technology it rearranges the order of units in the supply curve and changes the merit order dispatch. That effect is consistent with the theory that the subsidy exists to mitigate the inefficiency (deadweight loss) associated with an unpriced external cost, in this case the cost associated with greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. The subsidy itself creates a deadweight loss and an expense burden on taxpayers, but it's hard to tell if the benefits of reduced GHG emissions outweigh those effects. A comparison of the emissions reduction from technology substitution, evaluated at an estimate of the social cost of carbon, is the typical approach, and if that number exceeds the tax cost of the subsidy then that's the usual argument in favor of the subsidy.

Proponents of the PTC argue that it induces investments in units that will get used and not sit idle, because the PTC provides incentives for capacity utilization. But the PTC creates incentives for the wind generator to offer less than their true MC, which means negative offers. If there are enough wind generators in the market, and especially if those turbines have been built where wind is plentiful but transmission capacity is not, there can be hours where the market clearing price is negative and the wind generators will pay people to consume their energy.

This effect is the crux of the distortion because it induces the wind generator to make offers based not on their true MC, but on a synthetic MC that they perceive due to the opportunity cost of not “earning” the tax credit. These negative price periods tend to happen at night, so the pecuniary effect of these negative offers is to displace the technology that would be most likely to substitute for wind in the absence of wind: nuclear. Low-carbon nuclear. Which means that in those periods, the argument that the subsidy is internalizing the external cost of GHG emissions is irrelevant, because a non-emitting technology is substituting for another non-emitting technology. Over time this revenue loss has led to nuclear plant closures, and in states like Illinois and New York with politically powerful nuclear generators, to countervailing subsidies, so it's a form of a subsidy arms race. The reduction in market clearing price, both in negative price periods and by changing the shape of the supply curve, increases consumer surplus but probably reduces producer surplus.

The ITC incentives are possibly less distortionary from an energy markets perspective, but data suggest that the solar ITC in particular is the more costly for taxpayers. An investment tax credit does not provide the generator with a specific perception of a synthetic MC in the way that a PTC does, so it's less likely to distort market outcomes by distorting submitted offers. It does reduce the financial cost of investing in resources that are likely to have low marginal costs, so it will increase supply by adding units at the left of the supply curve, again increasing consumer surplus and reducing producer surplus while also incurring costs for taxpayers to pay the subsidy. The Joint Committee on taxation estimated that for “... 2020, the JCT estimated energy credit tax expenditures to be $6.8 billion, with the majority of tax expenditures ($6.7 billion) attributable to solar. Between 2020 and 2024, the JCT has estimated energy credit tax expenditures to be $35.5 billion, with $34.8 billion for solar.” In 2007-2011, the “section 45 and 48 credits combined are the single largest energy tax expenditure in the federal budget worth $4.1 billion over a five year period.” (Metcalf 2007, p. 162) In a little more than a decade that's an eight-fold increase in costs borne by taxpayers.

Metcalf's analysis also makes abundantly clear that oil and gas producers receive tax subsidies as well, which complicates Christie's narrative and muddies the supply curve even more. With this crazy quilt of subsidies, do we even know what a “true” merit order dispatch would be?

Do not forget that the theoretical argument for the PTC/ITC subsidies is to reduce the deadweight loss associated with unpriced greenhouse gas emissions by promoting renewable generation. Here Metcalf is blunt:

From a social welfare perspective, the production and investment tax credits are costly ways to encourage renewable electricity generation since the subsidies must be financed by raising distortionary taxes. An alternative approach to encouraging renewable electricity generation would be to place a tax on traditional fuels. As a final calculation, I computed the levelized cost of biomass and wind assuming no investment or production tax credits. In this case, the levelized costs of biomass and wind are 5.56 cents and 5.91 cents per kWh respectively. A tax on carbon dioxide of $12 per metric ton would raise the price of natural gas sufficiently to make biomass and wind cost-competitive with natural gas. Unlike the subsidies, however, the tax would raise revenue which could finance reductions in other distortionary taxes. (2007, p. 173)

The Political Economy of Subsidies

In other words, Metcalf is making the analytical claim that a revenue-neutral carbon tax would be a cheaper and more efficient way to achieve emissions reductions. The data from British Columbia's implementation of a revenue-neutral carbon tax suggests that, as with PTC/ITC subsidies, the political economy of implementation drives outcomes away from the blackboard neoclassical economic model. That means that another important piece of economic theory to apply here is public choice economics. I wrote about public choice, using economic models and methods to study non-market decision-making, a few months ago.

One strand of public choice theory is the science of special interest influence and lobbying. In this application it's no surprise that wind and solar generators have lobbied for the establishment and renewal of the PTC and ITC, even as their (unsubsidized) production costs have fallen to parity with other generators. And they have succeeded. Subsidies are considerably more expensive than a carbon tax with equivalent emissions effect would be, but those subsidy expenses are easier to obscure so that they aren't as obvious to voters. In our roles as elected representatives, we are still people and still make decisions based on our individual incentives. It's also no surprise that in British Columbia the payments to individuals to reduce their non-carbon tax burdens have receded, as other interests have argued for using the carbon tax revenue in some other way to support government spending. People are people.

Almost all energy technologies have some form of embedded subsidy that affects their owners' incentives, not just wind and solar. Federal wind and solar tax policy subsidies distort markets and require taxpayer funding so they are a costly way to internalize external costs, much more costly than a carbon tax. Political interests make subsidies attractive because they provide a revenue stream to recipients and they mask the costs to consumers/taxpayers of internalizing the external cost, while a tax would be less distortionary but more transparent and thus easier to block politically. We should eliminate subsidies and use different policy instruments to internalize external costs, and should exercise political leadership to communicate to people why that would, all things considered, be a less costly way to deal with GHG emissions. I don't expect subsidy elimination to happen, but it's important to be honest about how they are making markets function more poorly and are making it more costly for us to achieve our desired economic and environmental objectives.

Well balanced and thoughtful. Carbon taxes would be so much better, but as you say "people are people" which makes it difficult to get accepted.

David Fishman, who blogs and writes on X (Twitter) covers China's power policies extremely well.